|

Hi everyone –

We just had an amazing experience at the United Way Day of Caring 2018! The United Way Day of Caring is the single largest day of volunteerism of Thurston County! We were graciously picked as a project site. We were teamed up with StraderHallett, a Certified Public Accountant firm in Lacey, Washington. They had 9 employees volunteer for a full day of work, and boy did we put them to work! We are SO grateful for all they did for us.

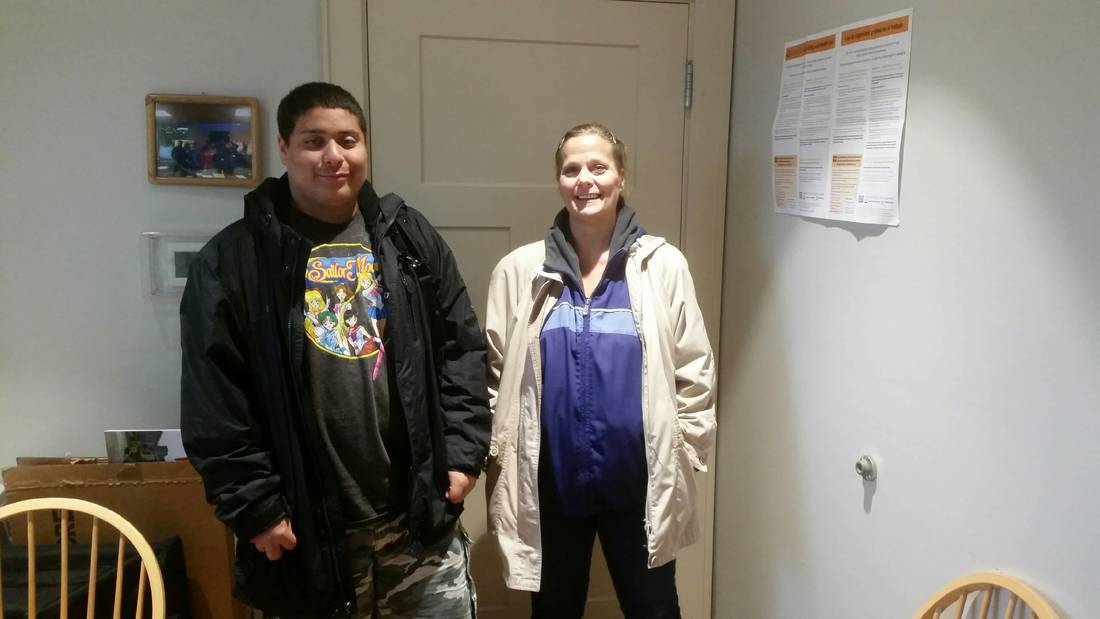

One of our residents who recently moved into her own home received the Phoenix Award from BHR! BHR is Behavioral Health Resources in Olympia, WA. BHR is a multi-county provider for mental illness and addiction recovery services. They offer therapy, outpatient treatment, psychiatry, crisis management, medication management, and many other services. As BHR states, “The Phoenix Awards are designed to celebrate those who have used their strength to rise from the ashes of mental illness and addiction, and, those who have helped them do so. By honoring and celebrating the achievements of these special people in our community, we hope to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness and/or addiction and to promote the understanding that mental illness and addiction is treatable. Sponsored by the BHR’s Community Mental Health Foundation and hosted by Olympia Federal Savings, this event celebrates lives made healthier through the skills and generosity of our community.” Congratulations Arin. We are so proud of you! Here is the nomination our Program Manager Raul Salazar wrote about Arin: Arin Long was one of the original residents of Quixote Village. She was a resident when the village was just a tent camp. She moved into Quixote Village on December 24, 2013 and was a resident until June 30, 2017. Arin had a long history of drug use, which was a major part of her life when she came to Camp Quixote. Many traumatic events in her life contributed to this addiction. As soon as she transitioned from the camp to Quixote Village, staff began working with Arin to provide her with the services needed to overcome her addictions. Arin struggled with the process of getting clean and sober, as many people often do. It was not easy and she was on the verge of losing her housing at Quixote Village on a few different occasions. Staff never gave up on her and Arin never gave up on herself. Despite going through not only her addiction to drugs, but also the loss of a close friend, Arin made the decision to enter a 60 day in-patient treatment program. She completed the program with flying colors and returned to Quixote Village, where her housing unit was being held for her. Upon her return, Arin began to involve herself in activities that would benefit her and others in various ways. She received her high school diploma through South Puget Sound Community College, she paid off existing court debt to renew her driver’s license, she attended regular recovery meetings, she obtained employment, and she purchased a vehicle. Arin also became a member of the Quixote Village Resident Committee. A group of residents that are voted onto the committee by other residents. The committee assists staff with daily tasks, provide guidance to new residents, and plan various resident social events. Arin was a major contributor to the committee. After all her success, it was clear to staff, that Arin was ready for life beyond Quixote Village. Although staff would have been happy to have Arin stay at the Village for much longer, she made the decision to move out and share a rental home with her significant other. Arin moved out at the end of June, 2017 and has continued to maintain her successful ways. She is excelling at her job and is enjoying the life she has created for herself. She maintains regular contact with Quixote Village residents and staff. It should be noted, Arin has been clean and sober for over two and a half years now. Arin is a great example of what can be accomplished when someone obtains stable housing and access to services. She is also a great example of hard work and determination. Although the process was difficult, Arin never gave up. She believed in herself and what she could accomplish. Quixote Village staff appreciate the opportunity to nominate Arin Long for an annual Phoenix Award. We believe she is very deserving of this honor.  Melissa and Aaron (Sustainability interns Spring 2018) Melissa and Aaron (Sustainability interns Spring 2018) Blog entry by Melissua Rasmussen - Quixote Village Spring Quater Intern Over the course of Spring quarter, two interns from the Evergreen State College, Melissa Rasmussen and Aaron Sauerhoff, met weekly with our Executive Director, Sean McGrady. They looked at the sustainability metrics of Quixote Village, how best to improve them, and how to design and build future villages to be even more socially and environmentally sustainable. Aaron’s specialty is ecological building and construction. He ran a blower door test of the tiny house cottages and the community building to see their airtightness and airflow. Aaron discovered the buildings could use some help with ventilation and wasted heat. He is recommending future villages be built to PassivHaus standards, which require a sealed air envelope around the building with careful ventilation and attention to recapturing heat, which provides a healthier home environment and significant cost savings (80% over utilities costs in a conventionally built structure). Implementing this change could save Panza tens of thousands of dollars per year in operating costs at the Orting Veterans Village. For future villages beyond that, improving the design to include solar power, natural construction materials, energy systems integration, and a more social and efficient village layout, could improve outcomes and reduce costs even further, and make Quixote’s model one that can be proudly shared and replicated as a model for sustainability. Over the summer, Aaron will be coordinating a Design Challenge for Quixote’s third community within a program at the Evergreen State College. Serving as Teacher’s Assistant (TA) to the Sustainability Director, Scott Morgan, Aaron will be in a position to further his work with Quixote Village while providing a real-world opportunity for students at Evergreen to engage in service to a community issue in a tangible way. A student at Evergreen himself, Aaron plans to graduate next year with a degree in Ecological Building and Community Development. Melissa specializes in system design and ecological thinking, and has worked with the Center for Sustainable Infrastructure at the Evergreen State College. She turned her attention toward assessing the landscaping challenges at Quixote, which range from shade issues, increased heat in the summer, and little sanctuary for individuals outside of their cottage homes.. Melissa brought in several classmates from Evergreen to make specific recommendations for shade and permaculture tree plantings, fixes to the lighting system to improve residents’ safety and sleep, and a gazebo to provide social relief and make good on what was originally planned. With these in place, she recommends incorporating these improvements into the design of future villages, and adding features such as a greenhouse attached to the community building to provide cooling, fresh air, delicious food, and a lovely place to sit all year round, saving food and heating costs and providing valuable opportunities for meaningful work and personal respite for the residents. Over the summer, Melissa will be working to formalize the team’s recommendations into a report, and to launch and run a crowdfunding campaign to provide Quixote with the funds necessary to invest in these improvements. She will also be continuing her studies at Evergreen in a context that allows her to continue her efforts in sustainable infrastructure development in Olympia and West Africa. She hopes to bring the evolved Quixote model to communities across the Northwest and beyond, providing the means for dignified, sustainable lives for all people everywhere – homeless, veterans, post-incarcerated, young families, youth, and seniors first. Melissa aims to graduate in 2019 with a degree in Ecological Design and Community Development. The two have made friends with several Quixote residents, including Tony, Bruce, and Brad, who showed himself very keen on the design of the gazebo. The pair attended community dinners and asked for comments and feedback from the residents, in order to make sure their solutions were aimed appropriately to address specific needs in the community. (Lighting, for instance, turned out to be a big one – several residents hang multiple layers of curtain to block the light from the miniature streetlight along their sheltered paths – there are ways to fix this!) Aaron and Melissa are both exceedingly grateful for the opportunity to work with Sean, Jaycie, Jill, and all the residents of Quixote Village, and hope to continue their work in support of the mission of Quixote Communities for a long time to come. Educational Program Evaluation: Quixote Village, Olympia, Washington ACE 640 July 2, 2018 Jennifer Binus Economic History/Background Information Regarding the Causative Situation for the Community Based Education Initiative Quixote Village’s story is really a tale of two cities: Seattle and Olympia. The Village became a reality because Seattle’s economic growth has led to a widening gap in income, which while creating jobs and stability for some, is harming the chances of stability for working poor. Economic instability has been found to decrease academic outcomes in children, negatively impacting their chances of success as adults, with a 26.2% less chance of graduating, and a 20-28% less likely chance of meeting age appropriate academic markers. Further, economic stressors related to unaffordable housing have been linked to individuals and families being forced to stay in abusive situations, lower quality food and medical care, and significant decreases in mental and physical well-being (WILHA, 2017). The area’s increase in population, drastic increases in rent, and stagnant wages for the working class have impacted areas as far away as Olympia and Bellingham. Western Washington has seen a significant growth in population in the last ten years due to economic growth in the Seattle area. Between 2010 and 2017, King County, home of Seattle, has seen a population increase of 222,451 individuals (Zhao, 2018). In 2011, the average 2-bedroom apartment cost $1,435 a month. Today, that same apartment costs $2,777 in Seattle (Rent Jungle, 2018). While King County hosts 1.21 million workers, averaging $76,830 in income in 2016, it is also home to 48,000 unemployed individuals (ESD, 2018). Thurston County, home of the state capitol, Olympia, is located 60 miles south of Seattle. Pierce County serves as a buffer between Seattle and Olympia, although Olympia still benefits from and feels the impact of Seattle’s population and economic growth and development. Thurston County has seen a population growth of 24,636 individuals since 2010 (Zhao, 2018). In Olympia, the rent on a two-bedroom apartment in 2005 was $937 a month, the same apartment costs $1,160 today, with a median rent of $1,136, not nearly as drastic a change as Seattle, but still expensive (TRPC, 2018). The average income in Olympia in 2016 was $63,286. Thurston County had 127,099 employed individuals and 6,658 unemployed individuals in 2016 (ESD, 2018). In 2016, the United State Census reported that 11.3% of Washington state residents lived below the poverty line, averaging $32,999 or less in income in a year. Lower paying jobs in this high rent community are partially to blame for the rise in homeless populations within these communities. While Thurston County is home to 579 sheltered, homeless adults, a decrease from 976 in 2010, and a school age homeless population of 1,600, an increase of 10% from 2016, of 149 students, King County is home to the third largest homeless community in the country. Washington state is home to 21,112 homeless persons. Seattle itself is home to 11, 643 counted unsheltered homeless individuals, (New York 76, 501; and Los Angeles 55,188) (Seattle Times, 2017). In 2017, the state increased housing by 39,500 homes to meet the need of this growth. This housing growth was an increase from the 34,600 units built in 2016, however, the overall growth of new housing is down from 43,500 at the beginning of the century. This is problematic for a state with a rapidly growing population. In 2016 alone, Washington state saw a population increase of 126,600 people, and while this did not account for individuals leaving the state, it still leaves a gap and a need for housing individuals and families (Zhao,2018). The Need Quixote Village is one of the original models used to shelter homeless residents in the nation with tiny houses. Quixote Village became a reality because a tent city in Olympia popped up in a downtown parking lot, “in solidarity with a tent city protest in Paris called the Children of Don Quixote,” in 2007, as a form of peaceful protest when Olympian officials forbade 30 chronically homeless adult residents from resting in the downtown area on benches or on the sidewalk and threatened them with arrest (Ransom, 2014). The community did not initially embrace what was then known as Camp Quixote, and the residents were forced to move 20 times over seven years due to zoning laws and restrictions. During this time, houses of worship became host to the community, as well as various out of the cold shelters, but nothing permanent was settled on until the state legislature, working with Panza, and the local church communities, approved funding for the 30 tiny houses to be built with the ultimate goal of the community being permanent housing for, “chronically homeless adults,” (Ransom, 2014). Quixote Village opened on Christmas Eve, 2013. Each tiny house is 144 square feet, and is “equipped with a toilet, a bed, a sink, and a front porch facing out on the shared green space,” (KCTS9, 2018). The community center, located on sight, offers a, “shared kitchen, and showers, and separate space for watching television, holding meetings or participating in the weekly yoga class,” (Quixote Village, 2018). In exchange for 30% of their income, residents are given a home, and a community. They are required to complete chores, keep their units neat, and be respectful of others. They are asked to work together to become members of the community they live in. The residents are linked with services which aim to meet their individual needs and goals, but educational services are optional, but strongly encouraged (Quixote Village, 2018). Definition and Type of Community-Based Education Initiative Quixote Village is a nonprofit organization whose primary goal is to house the chronically homeless. The program uses the Recovery Housing Model (Drug and Alcohol Free) and Permanent Housing Model (Residents may stay indefinitely, as they sign a lease and pay rent and will not be forced to leave due to time restrictions.) to run and maintain the program. Panza, (Poetically named for Don Quixote’s servant, Sancho Panza.) “is a 501C3, non-profit organization,” which supports the villagers, and helps residents by governing day to day operational affairs and works together with the Residence Council, made up of the community residents, for community betterment. Panza has an executive director, program manager, case manager, and an accountant. The Residence Council meets weekly to discuss and vote on matters concerning the community (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). While the community’s main goal is to house the area’s chronically homeless population, the community also serves as a means of educational opportunity to its community members. By providing residents with educational tools aimed at increasing their quality of life the program can offer sustainability education to its residents. The educational component of the programs’ primary goal is to increase the quality of life of residents during and after their stay in Quixote Village (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). Quixote Village provides optional educational programming to residents aimed at helping the individual become more self-sustaining. By working directly with The Peace Center (TPC) for educational purposes, Quixote Village is able to provide one on one case management to residents over a seven-week period, that is aimed at helping residents meet their overall educational goals and build skill sets that directly benefit residents and meet goals set by the residents with their case manager. Educators are able to teach basic life skills, such as money management, how to fill out a lease, balance a check book, basic nutrition, and other fundamentally important life skills that meet the needs of the individuals (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). The goal of the programming provided by the Peace Center, is to help the resident build life skills that will contribute to their overall success by assessing and understanding why the individual became homeless. Case managers are then able to determine immediate needs of residents and place them into programing to meet the specific needs of the individual, using their strengths to lead them to success (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). Programs that residents may participate in include, but are not limited to: “credit cards, loans, budgeting, nutrition, resume building,” as well as a new class on small business ownership. The program also provides information and assistance on, “job coaching, transitioning from homeless to community living, finding different providers and scheduling appointments, and renewing benefits,” (Osterberg, 2018). Further, the residents are linked to mental health, health, and substance abuse services as seen fit (Quixote Village, 2018). Effectiveness of Community-Based Education Initiative The one-on-one component is credited to the success of Quixote Village. Residents of Quixote Village have lived through a disproportionate level of, “trauma and abuse that has prevented them from living an independent life.” For some of the residents, their stay at Quixote Village is the, “longest they have ever lived in one place,” a success that case manager Jaycie Osterberg believes to be a huge success. This success is measured in the residents’ ability to live in one location and pay rent, a minimum of $50 a month, or 30% of their income (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). Educational goals are measured using HMIS, or the Homeless Management Information System of Washington State. This monitoring is mandatory and is used by the Department of Commerce. Resident income, mental and physical health are also assessed. Resident goals are put in place with the help of their case manager. Together, they assess whether or not the resident is meeting their goals based on progress the resident has made, and through resident self-assessment. Intake/exit interviews are used to determine how long residents may staying, where they go afterward, to check mental and physical health, determine substance use, employment, education, etc. (Quixote Village, 2018), (Osterberg, 2018). Finally, Quixote Village does not force occupants to leave, they may stay as long as necessary. Since 2013, Quixote Village has housed 61 individuals, of those 11 have moved on to permanent housing, and 5 have returned to the streets. The city of Olympia views the community with a positive outlook. Its success has led to a second village, which is in the process of planning and construction, Orting Village, which will be used for sheltering veterans (Quixote Village, 2018). Work Cited Coleman, V. (December 7, 2017). King county homeless population third-largest in U.S. Seattle Times. Retrieved from: https://www.com/seattle-news/homeless/king-county-homeless-population-third-largest-in-u-s/ Department of Numbers. (2018). Olympia, Washington: Residents’ rent and rental statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.deptofnumbers.com/rent/washington/olympia/ Employment Security Department: Washington State. (2018). King county profile. Retrieved from: https://esd.wa.gov/labormarketinfo/county-profiles/king Employment Security Department: Washington State. (2018). Thurston county profile. Retrieved from: https://esd.wa.gov/labormarketinfo/county-profiles/thurston Osterberg, J. (2018, June 27-29). Facebook interview with Jaycie Osterberg. Quixote Village.(2018). Quixote village. Retrieved from: Quixotevillage.com Ransom, T. (2014). Camp Quixote: Quixote village. Retrieved from: http://quixotevillage.com/camp-quixote-quixote-village-reposted-from-tim-ransom/ Rent Jungle. (2018). Rent trend data in Seattle, WA. 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.rentjungle.com/comparerent/ Thurston Regional Planning Council. (2018). Median household income. Retrieved from: https://www.trpc.org/460/Median-Household-Income Thurston Regional Planning Council. (2018). Thurston county homeless census report. Retrieved from: http://www.trpc.org/457/Homeless-Census United States Census Bureau. (2018). Washington state: Income and poverty. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/wa/PST045217 WILHA. (2017). Bringing Washington home. Retrieved from: http://wliha.org/sites/default/files/WLIHA%20Affordable%20Housing%20Report_FNL_for%20reference%20%281%29.pdf Zhao, Y. (2018). Population growth in Washington remains strong. Retrieved from: https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/legacy/pop/april1/ofm_april1_press_release.pdf  Article from Tim Ransom (former board present and current volunteer) in the Spring 2014 Special Edition Newsletter from The Olympia Unitarian Universality Congregation. Full Commons Newsletter (courtesy of Linda Crabtree of OUUC). The meetings of the Board and the Congregation [to vote on hosting Camp Quixote in February of 2007] were two of the most incredible and wonderful events in my life as a member of the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Congregation. The decisions were not easy—here we were essentially flying in the face of municipal code and laws, the wishes and fears of probably the vast majority of our neighbors, and our own fears and lack of understanding of the implications of what we were doing. And there was vigorous disagreement—while the goal of helping others was clear, how best to go about it while fulfilling our own rules of governance and protecting the congregation was fiercely debated. But in the end we acted with one heart and head.” I wrote that years ago, not long after the Board of Trustees of the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Congregation (OUUC) first invited a rag-tag group of homeless men and women and their political advocates to take up residence in tents on the lawn adjacent to our small Out of the Woods shelter for families. The import and impact of those first events stay with me today. The story of the development of Camp Quixote and its eventual evolution into Quixote Village deserves a full-length book!. Easily a dozen congregations and hundreds of volunteers have participated, and along the way many heroes have stepped up to take on the herculean tasks of coordination and support. Their stories deserve to be told, as well. But here I will limit myself to the part that our church congregation played in getting it all started. It all began when a delegation of Unitarian Universalist Evergreen students came to our February 2007 board meeting. They were from a group of homeless people and their activist supporters, the Poor People’s Union, who had set up an encampment on a downtown city lot in protest of a city ordinance that severely restricted the use of sidewalks, and they were being threatened by eviction, and more. We had agreed to meet with them to talk about providing the encampment temporary sanctuary on the front lawn below Out of the Woods. They wanted to move the camp there, and it was my job as board president, along with our minister, the Rev. Arthur Vaeni, to see if that could happen within the context of our congregation, its mission and its approach to decision-making and ministry. Quixote Village practices self-governance with elected leadership and membership rules. While a nonprofit board called Panza funds and guides the project, needing help is not the same thing as being helpless. As Mr. Johnson likes to say, “I’m homeless, not stupid.” - NYTimes.com  In hindsight it might appear that the obvious answer to this request from us as an Unitarian Universalist congregation would be “Yes.” But back then it quickly became apparent that there was a diversity of opinions about, and understanding of, homelessness and this particular iteration of it, tinged as it was by political activism. Then, too, we had serious concerns that the Board would be subverting the normal procedures of church governance if it acted without seeking the approval of the congregation and informing our neighbors first. After heated debate the Board reached consensus to offer sanctuary, and the next day the campers began their move to our property. Within days special congregational and neighborhood meetings followed;. Overruling the board’s intention to limit the camp’s tenure at OUUC to 45 days, an enthusiastic congregation voted to offer them a full 90 days. This, despite the fact that the Olympia City Manager warned us that as far as the city was concerned, an encampment on church property without a permit was just as illegal as the one downtown had been. The true test began, of course, when the encampment, now calling itself Camp Quixote, in solidarity with a tent city protest in Paris called the Children of Don Quixote, arrived on our property. As Rev. Vaeni will attest, pandemonium reigned. It had been a wet winter, and the Out of the Woods lawn immediately revealed its true nature as a wetland. Eventually volunteers provided truck loads of wood chips, and later pallets were used to keep tents out of the mud. It was apparent right from the beginning that the camp was going to need a great deal of help to survive and not implode. At first some of this was provided by the activist contingent, people like Rob Richards and Phil Owen of Bread and Roses, but then more and more members of our congregation quietly slipped through the woods to help set up tents, spread woodchips and welcome the residents. The presence of Camp Quixote on our property brought us many daunting challenges, not the least of which was the negative PR we were receiving from the local newspaper. But first and foremost on the list were negotiations with the City of Olympia to get a conditional use permit to legally host the camp (despite the fact that federal case law clearly indicated that faith communities have a constitutional right to provide such a ministry). Out of these negotiations came the rules regarding sanitation and safety procedures and eligibility for admission to the camp (background checks, no outstanding warrants, no use of drugs or alcohol, and so on) that were eventually to become features of the residents’ own self-governance. Another requirement was that the host church hold a community meeting to inform its neighbors of the camp’s coming and provide them an opportunity to voice concerns. Rev. Vaeni had already visited many of the neighbors and had learned that there was a great deal of mistrust and fear among them. Some even threatened to sue us if things went wrong. But the meetings proved to be a mixed blessing. While they were a chore, they were also a great opportunity, for the OUUC congregation especially, to get to know our neighbors and begin to build community with them. They were also an opportunity for the community to see growing support of the camp from city planning staff and police, who attended to help address our neighbors’ issues and attest to the validity of our approach. From the very start the camp’s residents and their supporters talked of finding a site where it could be set up permanently, perhaps on someone’s private property, perhaps at Evergreen State College. But time slipped by and nothing came of it. Meanwhile, Rev. Vaeni and members of our church began enlisting the support of other faith communities in the region. Eventually 14 religious leaders from eight churches, Temple Beth Hatfiloh, the Quakers, the Community for Interfaith Celebration and the Baha’i signed a letter exhorting the greater community to make a place in its midst for this response to homelessness and poverty, saying “Our willingness to reach out to those at the margins of society defines us as people of faith and morality. If we fail in this outreach, we fail our entire community.”  Suddenly we were on a countdown to the end of the 90 days OUUC was allowed to host the camp. Efforts to find another host were redoubled, and at the last minute volunteers from the United Churches of Olympia convinced their congregation and leadership to step up. Thus began the peripatetic adventures of Camp Quixote, as it moved every 90 days (later 180 days) from host congregation to host congregation, a prodigious labor that would sorely test the perseverance of the residents and of their many supporters, who time and again showed up to help dismantle and cleanup the encampment, truck it to the new site and then set it up again. Support of the camp truly became an interfaith activity as five faith communities in Olympia (OUUC, United Churches, St. John’s Episcopal, First Methodist and First Christian) and one in Lacey (Lacey Community Church) became hosts. Many others, including Temple Beth Hatfiloh, Westwood Baptist Church and the Muslim community, provided financial and logistical support, help with the moves and meals, and other forms of assistance.Recognizing from the start that the future of Camp Quixote would require an extraordinary level of coordination and cooperation, Rev. Vaeni began a series of faith community meetings late in February that engaged the participants, including lay leaders from the churches, camp residents and regional experts on homelessness, in educational and planning exercises. Eventually these gatherings gave rise to Panza (named after Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho Panza), a Camp Quixote support group originally made up of ordained and lay leaders charged with coordinating moves and hosting, facilitating the residents’ development of self-government, and pursuing the passage of supportive ordinances among the local municipalities. Fairly quickly, under the leadership of its OUUC representatives, including Selena Kilmoyer and myself, Panza established itself as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation and established a board of directors. The next few years saw a great deal of energy spent by the Panza Board and the supporters of the Camp to work out the logistics of host church scheduling and the providing of support by volunteers. It was apparent from the start that the best way to build support for the Camp was by encouraging people to visit it, meet the residents and help out. Moreover, as part of the original agreement with the City, volunteers were needed to staff a host table in the Camp 24 hours a day. This extraordinary commitment was initially made with the idea of protecting the neighborhood, but soon it became obvious that the real value was in providing security for the residents themselves. During this time, as well, a flood of friends of Camp Quixote, along with dedicated residents and Panza members, testified at public hearings as the local municipalities—Olympia, Tumwater, Lacey and Thurston County— one by one passed ordinances allowing for church-sponsored tent camps within their jurisdictions. Perseverance and growing community support were building a constituency. Over time the residents of Camp Quixote changed, as some moved on to more permanent housing, jobs, or opportunities elsewhere. Others found they could not obey the self-imposed rules of camp residency and had to leave. But despite these changes, one idea remained constant: to find a permanent site, perhaps one where tents could be exchanged for permanent structures. Eventually this concept became a guiding principle for Panza, and when I rejoined the Board in 2012, something truly amazing had happened. The Board had doubled in size to include both faith community members and professionals with expertise in architecture, finance and social work. At the helm was OUUC member and long-time volunteer, Jill Severn. And, Panza had just received notice that the state legislature had set aside over $1.5 million to build Quixote Village, a permanent supportive housing community for chronically homeless adult men and women! And Thurston County had promised to lease to Panza, for a dollar a year for 41 years, a 2.7 acre site in southwest Olympia upon which to build! The rest of the story is one of a community—the constituency built during seven years of fighting for and growing support for Camp Quixote—coming together to make the Village happen. There is not space here to list all the people, churches, businesses, elected officials and staff that went to extraordinary lengths to help, as we sought additional funding, responded to the concerns and then legal attacks of some of our neighbors in southwest Olympia, applied for permits, struggled with the limitations of the site and our funding—all the one hundred and one things a home builder must contend with, multiplied several-fold. And there were current residents of Camp Quixote who spent hours to help develop the concept and design of the Village, while all the time still facing all the difficulties of life in a tent. Our struggles were suspended on Christmas Eve, 2013, when the 30 residents of Camp Quixote became inhabitants of Quixote Village. |

contributorsArchives

November 2022

Categories |

|

Contact

Tax ID: 32-0243330 Panza dba Quixote Communities is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization that serves Western Washington. |

|

info@quixotecommunities.org | 360-338-0451 | 3350 Mottman Road SW Olympia, WA 98512

RSS Feed

RSS Feed